OORO: Why Are Our Boys So Angry? Netflix's ‘Adolescence’ Has a Chilling Answer

Through its gripping portrayal of a 13-year-old male caught in a situation beyond his control, the show delves deep into the complexities of family, identity, and how we confront the darker sides of ourselves.

In the face of shocking revelations, particularly those involving their children, many parents instinctively respond with denial: “Not my daughter,” “Can’t be my son,” or “This is insane.” Such defensive reactions are often a natural reflex to protect their child’s image and their own sense of identity. But what happens when the truth is undeniable, and the walls of denial begin to crack?

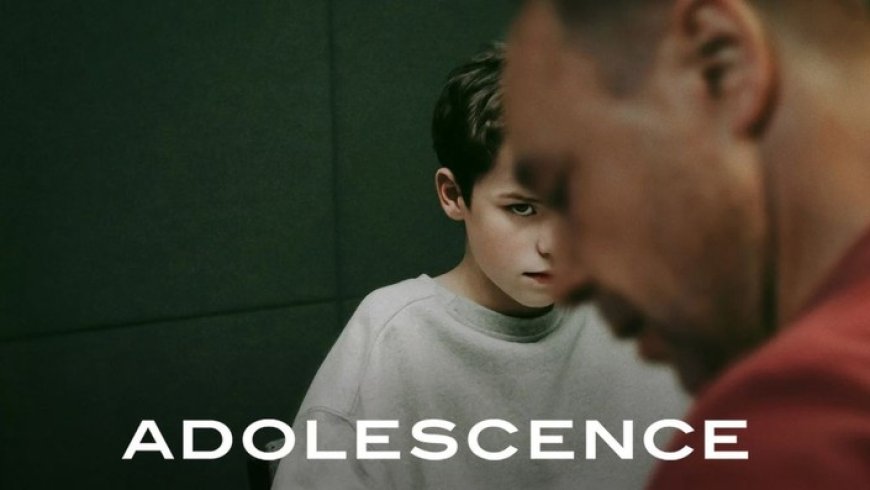

This dynamic is at the heart of Adolescence, the latest British hit mini series currently streaming on Netflix, which explores the turbulent, raw emotions of teen—rage, rebellion, and the painful transition from innocence to the harsh realities of justice system.

Through its gripping portrayal of a 13-year-old male caught in a situation beyond his control, the show delves deep into the complexities of family, identity, and how we confront the darker sides of ourselves.

By far Netflix’s most harrowing release of 2025, Adolescence is shot in a single continuous motion, and pulls viewers into the unraveling world of Jamie Miller, who is accused of murdering his classmate, Katie.

Erin Doherty and Owen Cooper in 'Adolescence'. /NETFLIX

Directed by Philip Barantini, the show begins with police storming into the bedroom of 13-year-old Jamie (Owen Cooper) in a northern English town, arresting him on suspicion of stabbing his classmate, Katie, to death. Co-creator Stephen Graham stars as Jamie’s father, Eddie, whose family is devastated by the shocking allegations.

While the first episode centers on Jamie’s arrest and entry into the criminal justice system, the second shifts focus to the investigation. Authorities search for the murder weapon and comb through Jamie and Katie’s social media messages to piece together the nature of their relationship. The gripping third episode centers on an intense exchange between Jamie and psychologist Briony Ariston.

The entire story unfolds over 13 months and concludes in the fourth and final episode, where Jamie makes an unexpected confession to his father.

So, why Did Jamie Kill Kate? Jamie killed Katie because of a combination of factors, including his lack of self-esteem, perceived bullying at school, and access to online incel propaganda.

During a counseling session, Jamie tells the therapist that he asked Katie out after a topless photo of her was sent among classmates on Snapchat as an act of revenge porn. But Katie rejected him and later sent emojis mocking him for asking. However, it’s after she publicly called him an incel on Instagram that pushes him over the edge. He stabs her shortly after.

The writers previously shared that the series was inspired by the knife-crime epidemic in the U.K. and an exploration of male rage.

Stephen Graham told Vanity Fair, a US culture magazine, that he was initially unfamiliar with the 'manosphere'—a controversial network of websites, blogs, forums, and online communities centered on men’s rights, male interests, and opposition to feminism.

Jack Thorne, another co-creator of the show, told a US newspaper, the Los Angeles Times, that he wanted to move beyond the typical narrative of blaming the parents. Instead, he sought to examine other factors that could influence Jamie’s behavior, including the rise of incel culture online. The Anti-Defamation League, defines incels as “heterosexual men who blame women and society for their lack of romantic success.

After Jamie admits his guilty plea, his parents have a heartfelt conversation about where they went wrong. Manda raises questions about Jamie’s temper and regrets not monitoring his computer usage more closely, while Eddie is still traumatized by the CCTV footage of the murder.

In the final scene, Jamie’s father steps into his son's untouched room and breaks down, burying his face in his pillow. He apologizes to Jamie’s teddy bear, a symbolic stand-in for his son. “I’m sorry, son, I should’ve done better,” he says.

Thorne added that the series was also driven by an exploration of male rage. As he, Graham, and director Philip Barantini reflected on their own identities as men, fathers, partners, and friends, they found themselves “questioning with some intensity” who they were as people, and specifically, as men.

“That is a journey I’ve never gone on as a writer before, and it scared me and excited me because it felt like we had something to say," he said.

Graham told Vanity Fair that he was initially unfamiliar with the concept of the manosphere—a controversial network of websites, blogs, forums, and online communities centered on men’s rights, male interests, and opposition to feminism.

Over the last three decades, the Kenyan boychild has been left behind in Kenya’s economic and cultural development, and this has perpetuated local discourses about the ‘neglect of the boychild’. Most development aid interventions have always targeted the girlchild, and women have increasingly been empowered economically.

As a result and in retaliation to the world becoming more 'femicentric', the masculinity consultancy scene has become a booming business with controversial figures such as Andrew Kibe, Amerix, Jacob Aliet, Silas Nyanchwani, who give 'masculine' advice to Kenyan men on Twitter and through their books and social media channels.

Collage of Amerix (left) and Andrew Kibe (right). /X

While all four align with the global red pill movement, part of a global backlash against feminism or some of feminism’s social consequences, they do so to different degrees. Amerix and Andrew have a more radical take on Kenya’s gender relations and offer answers that aim at changing not only the totality of his adepts’ daily lives but also openly admire Paul Kagame’s autocratic style of leadership and dreams of a world where strong ‘Afrikan’ men subdue obedient women.

Such radical anti-feminist rage via social media is doing more harm than good to society. Male children, as young as 10, are now bossing their female counterparts in schools, churches and other social gatherings -- saying hurtful things, excluding peers, and acting in other unkind ways.

They are not acting mean on purpose. By and large, these kids are struggling with difficult feelings of insecurity/self-doubt and anxiety perpetuated by the self-awareness campaign propagated by the likes of Amerix.

These complex emotions are uncomfortable and hard to make sense of and cope with, even for adults, no less young children who don’t have the self-awareness or skills to deal with these emotions effectively; so, they act them out via projection—attributing uncomfortable emotions to others.

They project these difficult emotions that are hard for them to tolerate onto others, moreso the weaker opposite sex. It's a coping mechanism, albeit an unhealthy one.

Ooro George is a Kenyan journalist, blogger, editor-at-large, art critic, and cross-cultural curator. You can reach him via LinkedIn here, through email: oorojoj@gmail.com and on X @OoroGeorge